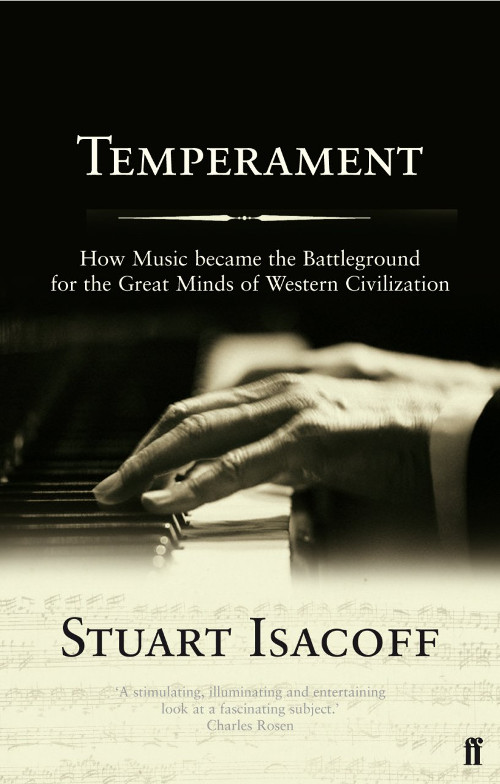

As a follow up to my recent book review of Stuart Isacoff's Temperament: How Music Became a Battleground for the Great Minds of Western Civilization, I'd like to share a podcast from the folks over at Between the Liner Notes. The episode is called “The Tuning Wars.” In the episode, the host, Matthew Billy, interviews Stuart Isacoff who elaborates on various aspects of the book.

Billy begins with the effect that Temperatment had on the public immediately following publication. People across the world lashed out at Isacoff, attacking him via blog posts, tweets, and Amazon reviews. One opponent may have even gone as far as comparing Isacoff's language to that of the Third Reich. To many, the issues discussed in Temperament are far from resolved and these people took Isacoff's claims as an attack on their beliefs.

The most interesting part of the podcast is when a portion of a Bach composition is played with several different tunings and in different keys: first with Pythagorean tuning and in a key that the piece was not intended to be played in, second with Pythagorean tuning and in the key that the piece was intended for, and finally in Equal Temperament.. Here, the listener can actually hear what Isacoff's entire book is dedicated to describing – the “wolf” intervals, the beautiful harmonies, and the compromise between the two. In addition, Billy describes the origin of the word “temperament” and its relation to the system of medicine known as “humorism” common to ancient Greek and Roman societies.

The Catholic Church was fiercely loyal to the Pythagorean tunings. The Church believed that the “godly” whole-number ratios that formed consonant musical intervals were a gift from Christ himself and were not to be tampered with. At one point, there was even a “Battle of the Organs” in which two leading organ-builders with differing opinions on temperament competed for their instruments to be permanently installed in London's Temple Church. Calling it a “battle” is only a slight overstatement, as one side went so far as to sabotage the other's organ the night before the contest.

Many famous names were involved in the battle of Equal Temperament. Galileo's father, Vincenzo Galilei, had a long and bitter dispute about the topic with his teacher Gioseffo Zarlino which often devolved into one attacking the other's character. Isaac Newton and Johannes Kepler respectively claimed that the intervals of western music were proportional to the distance between colors in the spectrum of light and between planets in the solar system. Kepler went as far as to attribute male qualities to certain intervals and female qualities to others.

Between the Liner Notes does a fantastic job of expanding on some of the most interesting points from Temperament. I highly recommend listening to the podcast in full and am looking forward to their next episode this coming Monday.

Listen to the full podcast here:

http://www.betweenthelinernotes.com/episodes-1/2015/9/1/02-the-tuning-wars

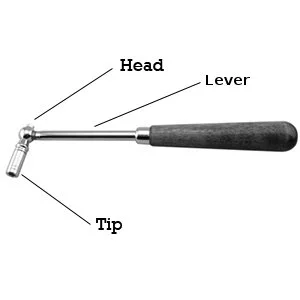

I have been servicing and tuning pianos in NOLA since 2012 after first becoming interested in piano technology in 2009. With a background in teaching bicycle mechanics, I bring a methodical mindset and a love of sharing knowledge and skills to the rich musical culture of New Orleans.